The Liberty project made its first public presentation in Sydney on 24 September, as part of the Animal Justice Party’s annual conference, coinciding with International Rabbit Day. Founder of the Liberty project, Paula Wallace, presented the case for an independent ‘Liberty’ movement in Australia supported by research institutions, as a more sustainable and ethical approach to managing non-human animals in research.

Here is a transcript of the presentation, with accompanying slides.

It’s great to be among like-minded people today for this day of action. And I think anyone who is here today is taking action towards ending suffering, but more than that, in promoting understanding.

This is an auspicious occasion for another reason, this is the first public presentation for the Liberty project in Australia, one I hope of many more.

If there are three things that you take away from my presentation today, I hope it’s that:

. Every ex-research animal that can have a good life, should have one

. This is already happening successfully overseas

. We all need to work together to make this happen in Australia

So what is the Liberty project or Liberty movement?

Well, over the past ten years we have seen a number of sanctuaries, involving public, private and charitable organisations, set up to care for animals from research institutions. For instance, Gut Aidebichl in Austria; Chimp Haven in the US; Fauna Foundation in Canada; Beagle Freedom Project in the US and Australia; and New Life Sanctuary in California – are just some examples.

So, Liberty movement is simply a term of that I’ve coined to describe this growing phenomenon, which we are hoping to bring to Australia in the form of specialist independent facilities, or Liberty Centres, with the support of research institutions.

These sanctuaries overseas are not just for primates such as chimpanzees. New Life Sanctuary is a successful example of a rehoming option for companion animals, rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs and farm animals.

My background is in business journalism and communications, where I’ve written extensively on sustainability and environment issues and corporate sustainability reporting.

But let me backtrack a little bit…

When I was in High School, I did my Year 10 work experience at a university in Sydney. I was interested in working with animals and was granted permission to spend a week with the animal attendant working with the rodents and other species being used for scientific purposes.

Whilst there I saw researchers carrying out their work and was involved in the capture of three wallabies as part of a university-funded research program. Two of them were subjected to vivisection that day, a procedure that resulted in their deaths. The third one, having heard what was quite a noisy procedure, was waiting to meet the same fate. I placed my hand on the outside of the hessian bag that contained the live wallaby.

The next day when I came into work I was told by the animal attendant that due to my “behaviour” the day before they would not be permitting work experience students in future.

I received the news in silence, I was 16 years old and I simply didn’t have the words to respond or to even understand the issues that had been stirred by such a small, instinctual act on my part.

Let me be clear, there are no goodies or baddies in that story, but I think it’s an accurate analogy, even 30 years on, for what happens when intellect meets intuition; when two worlds collide and there is no shared language or understanding.

This is really what Liberty Project hopes to achieve. To create that shared language… where research institutions can talk about their work with animals and consider the values and opinions of the broader societies within which they operate.

It’s going to be impossible for research institutions to be part of creating a shared language if they don’t speak, which is why part of my presentation addresses issues around openness and transparency.

We’ve seen a situation emerge where research institutions use the activities of some animal advocates to justify maintaining a defensive agenda – then activists use this to justify their campaigning. And so it goes on, a viscious cycle.

There is an acceptance from the scientific community internationally that confidence in its research rests on it embracing an “open approach and taking part in an ongoing conversation about why and how animals are used in research”.

The life science sector in the UK believes that as a world leader in research it has to gain the public’s trust which requires it to be “open, transparent, and accountable” for the research it conducts, funds or supports.

We’re hoping Australian researchers will take advantage of the benefits of joining this conversation.

But we’re certainly not the first ones to be doing this. There has been great work already done by animal advocates and scientists over the past 50 years or so, to bring the work of animal-based science into broader discussion.

This can only lead to better outcomes for animals and for research institutions and has been gaining momentum in recent years on several fronts, mostly in Europe and the US. Namely, greater openness and engagement on behalf of the scientific community and life sciences sector as I’ve mentioned; greater commitment to the reduction and replacement of animals in science; and the pursuit of legal avenues to have the personhood of animals recognised.

Most interestingly, there have been moves by government and industry overseas to provide more ethical and sustainable options for animals at the conclusion of research.

In May 2014, Minnesota became the first state in the US and first political body in the world to mandate that laboratory dogs and cats be adopted when the research is completed. If a dog or cat is used in a taxpayer funded research experiment and is healthy at its end, the organisation must offer them up for public adoption through an organisation like Beagle Freedom Project.

In November last year, it was reported that the chimpanzees still used by the United States’ National Institutes of Health for animal testing would soon be sent to sanctuaries for their “retirement” as the US governmental medical research agency ceases its chimp program altogether. Upon retirement, the chimps will be sent to Chimp Haven – a partly government-funded facility in Louisiana that currently houses more than 200 chimps. There are also a number of other, similar facilities in Europe and Canada.

In Australia, the national code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes states that opportunities to rehome animals should be considered wherever possible.

Unfortunately, many research institutions and their animals ethics committees do not generally consider that there are suitable options for rehoming. This is where Liberty Centres can play a vital role in enabling research institutions to better align with government requirements and public values when it comes to animal welfare.

Based on my research over the past year, I have produced a white paper which makes the case in detail for a Liberty movement in Australia supported by research institutions. You can download a copy at this address.

But we still need to find out much more about the kinds and numbers of animals that could be rehomed.

It’s worth noting that the term research institution is a general term used in the context of this presentation and the white paper for simplicity sake. So when I say research institution, I’m referring primarily to: universities; government agencies; companies such as pharmaceutical; and biomedical research foundations.

Anyone with an interest in this area will know that it’s difficult to characterise an animal-based research sector as such, the companies and organisations that work with animals for scientific purposes are diverse.

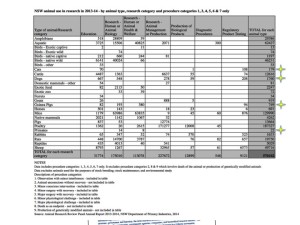

At the moment we have access to basic data which give some insight into the numbers of animals used for different kinds of procedures but often does not classisfy them by species or by indicators that would allow us to assess their suitability for rehoming.

Of an estimated 7 million animals used for scientific purposes in 2014, around 1.62 million would have theoretically been available, but not necessarily suitable, for rehoming.

If we have a look just at the figures from NSW, once we remove the animals that die during the course of research, we can get some idea of the kinds of animals that may be able to achieve good quality of life post-research. You can see here, there are 179 cats and 1,760 dogs, 749 guinea pigs, 22 primates, just to name a few.

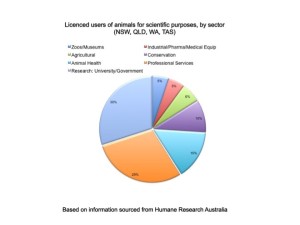

Based on information provided this year by governments in NSW, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania, the breakdown of facilities licenced to use animals for scientific purposes is shown in this pie chart.

We’re most interested in the research at university/government level (30%); agricultural (6%); animal health (5%); and industrial/pharmaceutical research and medical equipment (5%) – so those groups together make up around 46% of all the licenced facilities.

Out of all these research institutions, we estimate that around 6% were publicly listed and less than half of those with the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX); a further 11% were university owned or operated; 13% were not-for-profit or community- owned; 13% were government owned or operated; and the remainder (57%) were privately owned or employee-owned.

While this provides some indication of the share of animal-based research conducted in different sectors, it does not allow insight into individual animals and their involvement. It is also complicated by the fact that information from Victoria is missing and we know that it is home to about 150 biotechnology companies, as well as 13 major medical research institutes, 10 teaching hospitals conducting significant research, and nine universities. Victorian companies make up 68% of the aggregate value of Australia’s top 20 listed biotechnology companies, including Australia’s largest, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL).

Much of the basic science conducted in Australia is supported by taxpayer-funded grants through the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council, some of which involves animals, but we don’t know how much. Universities were the primary recipients of current funding (more than 65% from the NHMRC and 100% from ARC), with the remainder going to research institutes and government agencies.

So, why would these research institutions support the Liberty movement? The answer is simple: they can only benefit from supporting rehoming options for animals, where they take a proactive approach that acknowledges their responsibility and reflects public and stakeholder values. The Liberty Project in Australia ticks all those boxes.

Here are the primary benefits that we’ve identified to date, they range from competitive advantage and better risk management, to an increased capacity to meet government regulations and align with global trends.

We are actually in the very early stages of talking to Animal Ethics Committees about the Liberty Project and getting their feedback. Clearly, without their support it won’t be possible to provide other options for animals post-research.

But the case for rehoming reaches beyond the mandate of ethics committees. The growing awareness within the financial sector of the problems associated with animal welfare (such as factory farming) demonstrates the risks and opportunities for those organisations that have chosen to proactively engage on these issues at a leadership level.

An article in The Guardian, in March, says that following the success of the fossil fuel divestment movement, campaigning is now targeting investors that support factory faming and more generally highlighting the risks of companies directly and indirectly exposed to harmful practices.

The Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare (BBFAW), set up in part by the NGO Compassion in World Farming, says more than half of the world’s leading food companies have now published targets on farm animal welfare.

New Life Animal Sanctuary in California also works with university student groups to lobby their schools to follow a more humane path and choose sanctuary over euthanasia.

With animal welfare issues being elevated to national importance in Australia in recent years, it’s not hard to imagine the welfare of research animals attracting similar scrutiny. And support of the Liberty movement gives research institutions a more sustainable way to manage animals under their care than the current widespread practice of euthanasia.

It’s not impossible to achieve. History is full of stories where the most unlikely allies have come together to create change.

Who could forget the historic $1m donation, made in 1981 by the Cosmetic, Toiletry and Fragrance Association in the US that led to the creation of the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing. Due to the money put up by companies such as Revlon, Avon, Max Factor, Chanel and others, companies that were testing their products on animals, the Center remains one of the leading institutions for replacing animals in science today.

Then there is the incredible journey of the 38 chimpanzees that now reside in a sanctuary in Austria. This was made possible in part by the pharmaceutical company BAXTER deciding to take, and I quote, “moral responsibility” for the animals when it inherited them as part of canadian online gambling an acquisition in 1997. Despite its first attempt to rehome the chimps collapsing when an animal sanctuary went bankrupt, the Austrian government continued to work on solutions and was able to bring together a number of organisation in partnership with BAXTER to establish a $3m outdoor facility for the chimps where they will be able to live out the course of their natural lives.

I understand that rehoming sanctuaries or centres will only be able to care for a fraction of the animals used for scientific purposes in Australia. But, I do think they will play an important role in placing greater awareness and value on the lives of animals; and in assisting research institutions to create internal culture change and better align their activities with public and stakeholder values, international trends and government requirements.

The reality is, that wherever you sit ethically in regard to animal-based research, these creatures exist and their needs are immediate. I don’t believe their lives should be invisible and their options limited, simply because we can’t find a shared language for talking about them. If we have a conversation based on honesty and open mindedness, then the future for these creatures, both great and small, changes radically.

I’m prepared to take up that conversation. But we need to add more voices if we are to have an impact.

Perhaps theres’s someone you know at a university or an animal ethics committee who you think might be interested in learning more about the Liberty Project.

Maybe you have ideas about how we can engage pharmaceutical companies or biomedical research in the idea of rehoming centres. Whatever ideas you have, we’d love to hear from you.

Right now, we are establishing all those networks, with the view of securing funding from research institutions and government, and also identifying new or existing sites where we could possibly establish rehoming centres in NSW and Victoria.

While we are focused on the research institutions, as we see how this can enhance their sustainability strategies and fulfill their responsibility to the animals in their care, we are also interested in speaking with other potential patrons, benefactors and sources of funding.

Another way you can help, is to support the Animal Justice Party.

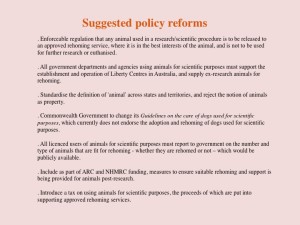

From a policy perspective there are many changes that would improve the situation for animals involved in the research supply chain.

The Liberty Project does not take a position on issues other those related to rehoming of ex-research animals, and in that vain we suggest the following policy reforms [see slide].

These policy suggestions and the white paper highlight the fact that we all need to work together to bring the Liberty movement to Australia and create a better future for ex-research animals: that includes research institutions, animal advocates, governments and people who care like you and me.

Thank You.

Comments are closed.